Medtner & Rachmaninov: Piano Sonatas

Steven Osborne (piano)

CDA67936

Steven Osborne has become increasingly admired for his performances and recordings of Russian Romantic piano music, playing with a remarkable level of authority and a rare combination of technical ease, tonal lustre and idiomatic identification. Here he presents an impressive selection from two masters who lived and worked contemporaneously. Both were renowned concert pianists, and both wrote superbly for their instrument. Yet their reputations could not be more divergent. Rachmaninov utterly loved; Medtner only now becoming rehabilitated.

Medtner’s ‘Sonata Romantica’ was composed in 1930 in Paris, and first performed by the composer in Glasgow the following year. It was the twelfth of his fourteen piano sonatas. Not only its title but also the expressive content of its four movements, played without a break, make it virtually a manifesto for Medtner’s art. Apart from sonatas, Medtner’s favourite genre was the Skazka (‘Tale’). It has been pointed out that the usual English translation of ‘Fairy tale’ does not do justice to the power and depth of many of these pieces, some of which almost approach Chopin’s Ballades in their expressive scope. The two Skazki of Op 20 recorded here were composed in 1909.

In a recent performance of Rachmaninov’s Piano Sonata No 2, a great Romantic showpiece, Osborne was described by the Washington Post as ‘a master of momentum and color, a wielder of power and a sure navigator through huge landscapes: his Rachmaninov was both coherent and daringly free’.

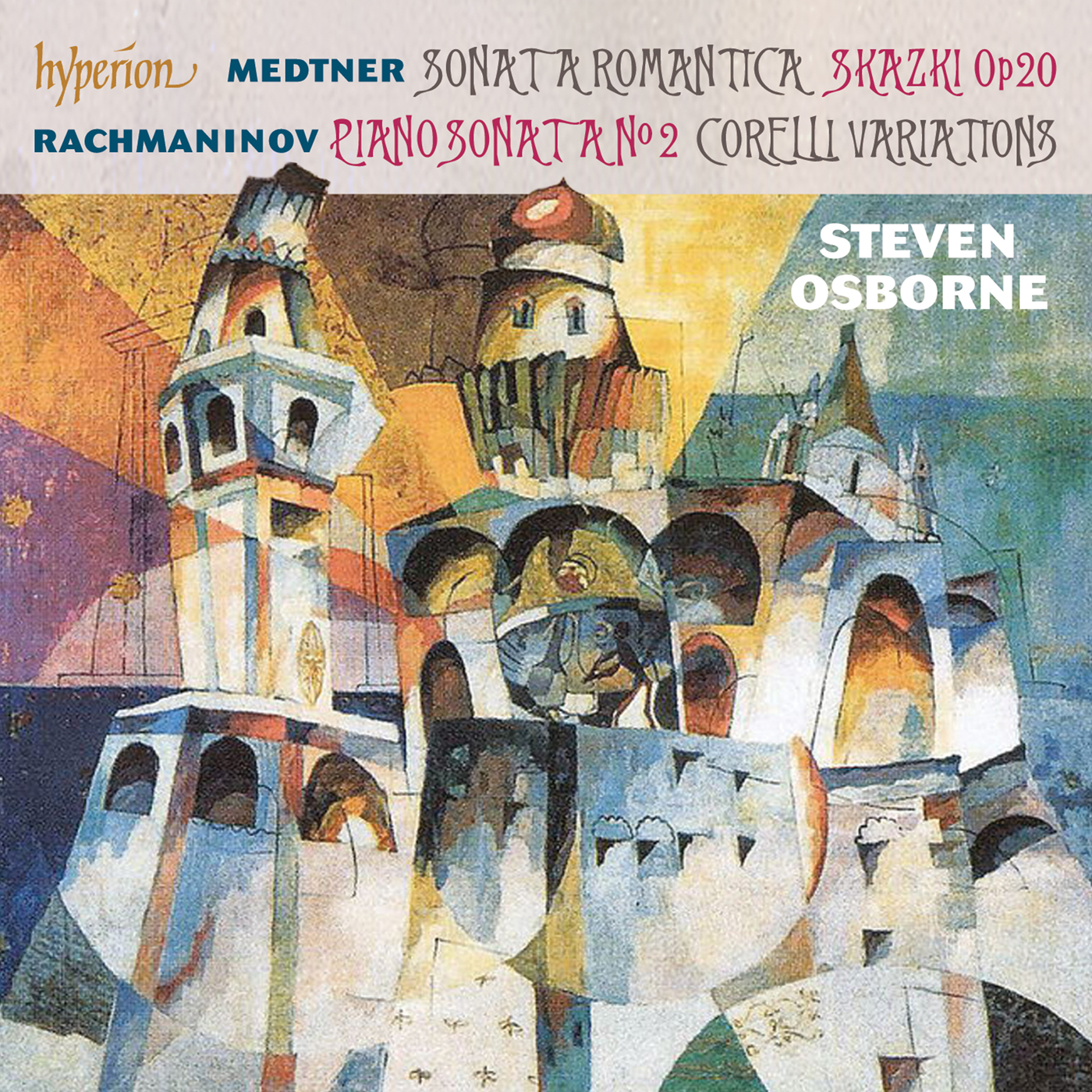

Behind The Cover

Revolutions and artists sometimes clash or learn to rub along. While both Rachmaninov and Medtner, the composers on this album, abandoned the Soviet Union, the artist behind this cover appears to have thrived within its strictures.

Those composers who stayed in the Soviet Union had to adapt their compositional style to avoid official censure, but avant-garde Russian Futurist painters like Aristarkh Lentulov seem to have been able to navigate these political waters more easily, and even thrived. Why? Perhaps the Soviet state found in Russian Futurism a boldness of style it could simplify and adapt for its weighty propaganda machine. Contemporary painting was co-opted for state purposes.

By contrast, musicians like Nikolai Medtner, admired by contemporaries but by temperament unable to provide the state with music it could use, fell from favour. He settled into a quiet life of teaching and lecturing in London from the mid-1930s.

Lentulov meanwhile was very much the doyen of Russian Futurism and rose to become Chairman of the Moscow Society of Artists. Virtually an exact contemporary of Nikolai Medtner, he was a major influence in the Russian Futurist movement that spawned artists such as Wassily Kandinsky. This painting 'Ivan the Great Bell' (1915) is a typical example of Lentulov's work, drawing influence from the folklore, monuments and architecture of Russia.